Army collaboration develops new class of materials that could unlock capabilities for batteries, water filtration (DEVCOM ARL News)

Research develops new polymer material that self-assembles into 2D sheets

U.S. Army DEVCOM Army Research Laboratory Public Affairs

RESEARCH TRIANGLE PARK, N.C. – An Army collaboration demonstrated a novel approach, once thought impossible, for the synthesis of a new class of high performance polymer materials. This sheet-like polymer forms films stronger than steel and as light as plastic, with the potential to revolutionize a wide range of Army systems.

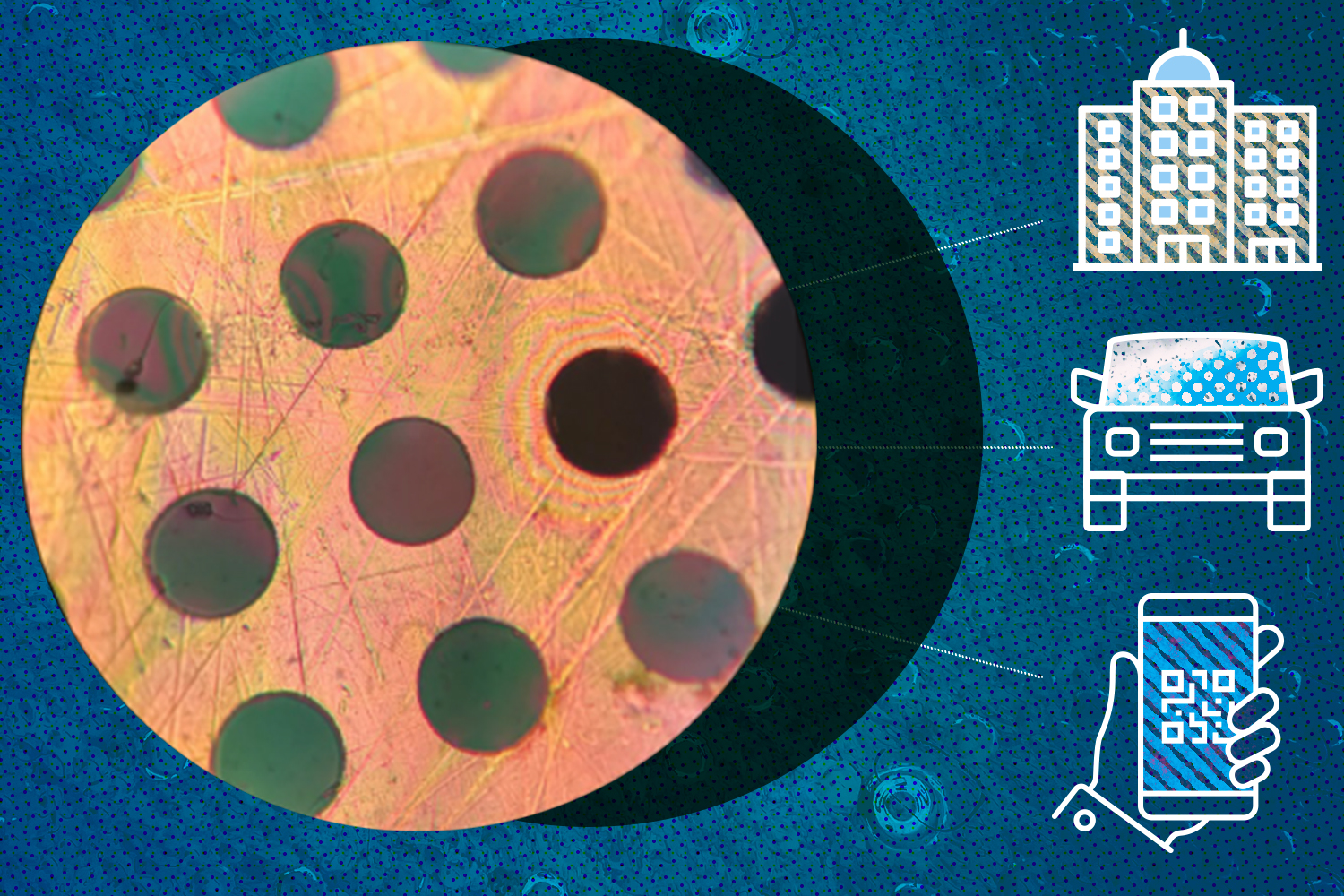

The material, developed by researchers at U.S. Army’s Institute for Soldier Nanotechnologies at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and the U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command Army Research Lab, is a two-dimensional polymer that self-assembles into molecular sheets. These new 2D polymers form strong films because the sheets orient and layer like bricks in a wall, with attraction between the sheets acting as the mortar. The research is published in Nature.

Polymers are large molecules made from repeating links called monomers. For many decades, polymers — such as those in all plastics — were formed either by linking one monomer to the next to form a molecular chain or by joining them into a jumbled three-dimensional network. About 15 years ago, scientists discovered how to assemble monomers into well-organized, honeycomb-like sheets instead of chains. A necessary condition for forming these 2D polymers, it was believed, was the use of reversible reactions that would allow the monomers to form and un-form over many cycles in order to settle in to a regular, repeating molecular structure.

In the new study, the MIT and Army team found that 2D polymers could instead be formed using irreversible polymerization: the monomers have only one opportunity to bond and, once joined, will not separate, defying conventional wisdom.

“This mechanism happens spontaneously in solution, and after we synthesize the material, we can easily spin-coat thin films that are extraordinarily strong,” said Dr. Michael Strano, Carbon P. Dubbs professor of chemical engineering at MIT and senior author of the study.

The films produced in this study are particularly useful because of the pervasive presence of attractive forces between the molecules, leading to unusual levels of chemical, mechanical, and thermal resilience. The importance of these intermolecular forces for creating high performance molecular sheets was hypothesized in a 2018 publication in Scientific Reports by DEVCOM ARL scientists Dr. Eric Wetzel and Dr. Emil Sandoz-Rosado, who are also co-authors of the new study.

"By teaming with MIT, we were able to show that 2D polymers with strong intermolecular bonding were not just a theoretical possibility, but a real opportunity for improved materials," said Wetzel.

The researchers found that the new material’s elastic modulus — a measure of how much force it takes to deform a material — is between four and six times greater than that of typical engineering polymers. They also found that its yield strength, or how much force it takes to break the material, is twice that of steel even though the material has only about one-sixth steel’s density.

Another key feature of this material is that it is impermeable to gases. While the coiled chains of other polymers feature gaps through which gases can seep, the new material’s monomers lock tightly together like LEGOs, preventing the passage of molecules.

“This could allow us to create ultrathin coatings that can completely prevent water or gases from getting through,” said Strano. “This kind of barrier coating could be used to protect metal in cars and other vehicles, or steel structures.”

These 2D polymer sheets can be designed and tuned for a lot of applications, said Sandoz-Rosado.

"Applications could include faster-charging batteries, and filters that block contaminants to make drinking water more accessible,” Sandoz-Rosado said. “Future modifications to the synthesis process should allow for the formation of 2D polymers with regular, aligned pores. These pores can be engineered to be large enough to allow water to flow through the films but small enough to block contaminants or, in the case of battery separators, allow fast charging through an electrolyte while preventing electrical shorting.”

The Army was an early proponent for basic research into 2D polymers, including supporting a Multidisciplinary University Research Initiative focused on unlocking new electronic properties in 2D polymers. The MURI program supports research teams whose research efforts intersect more than one traditional science and engineering discipline. This prior work established many of the foundational principles for 2D polymer synthesis that motivated the MIT study.

“I know I speak for the entire team in saying that we are excited to work on materials science that will eventually save lives once processed for Soldier and vehicle equipment,” said Dr. Jim Burgess, the DEVCOM ARL program manager for the Institute for Soldier Nanotechnologies. “Improved materials are key to enabling revolutionary capabilities that reduce the weight burden sustained by soldiers and ground-vehicles, enhancing battlefield operations and lowering energy costs. The DEVCOM ARL intramural and extramural partnership with academia was critical to this advancement.”

The U.S. Army established the MIT Institute for Nanotechnologies in 2002 as an interdisciplinary university-affiliated research center (UARC) focused on dramatically improving the protection, survivability, and mission capabilities of the Soldier and of Soldier-supporting platforms and systems.

In additional to ARL, the research was funded by the Center for Enhanced Nanofluidic Transport an Energy Frontier Research Center sponsored by the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science.

Visit the laboratory's Media Center to discover more Army science and technology stories

As the Army's foundational research laboratory, ARL is operationalizing science to achieve transformational overmatch. Through collaboration across the command’s core technical competencies, DEVCOM leads in the discovery, development and delivery of the technology-based capabilities required to make Soldiers more successful at winning the nation’s wars and come home safely. DEVCOM Army Research Laboratory is an element of the U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command. DEVCOM is a major subordinate command of the Army Futures Command.